On October 5, 2025, Iran’s parliament took a historic step by approving legislation to remove four zeros from the national currency, marking a pivotal moment in the country’s economic history. This decision, which had been debated across three administrations and three parliamentary sessions, represents more than a simple numerical adjustment—it symbolizes Iran’s entry into a new economic experiment that has been tested in dozens of countries worldwide with mixed results. The reform officially brings back the “qiran” as a subdivision of currency and restructures Iran’s monetary system without changing the official name of the currency, which remains the “rial.” While proponents argue this change will facilitate transactions and restore national dignity, critics warn it amounts to cosmetic surgery without addressing the underlying disease of chronic inflation.

The Legislative Journey: Three Governments, Three Parliaments, One Decision

The path to this reform was anything but straightforward. As Shams al-Din Hosseini, Chairman of the Parliament’s Economic Commission, explained in his floor speech: “What the parliament is reviewing today has gone through three governments and three parliaments.” The legislation was first introduced during the twelfth government and passed by the tenth parliament, only to be returned by the Guardian Council due to ambiguities regarding Iran’s commitments to the International Monetary Fund. The eleventh parliament resolved these issues, but the bill never reached the floor for debate. Finally, with the fourteenth government and twelfth parliament in session, the review process resumed and culminated in today’s approval.

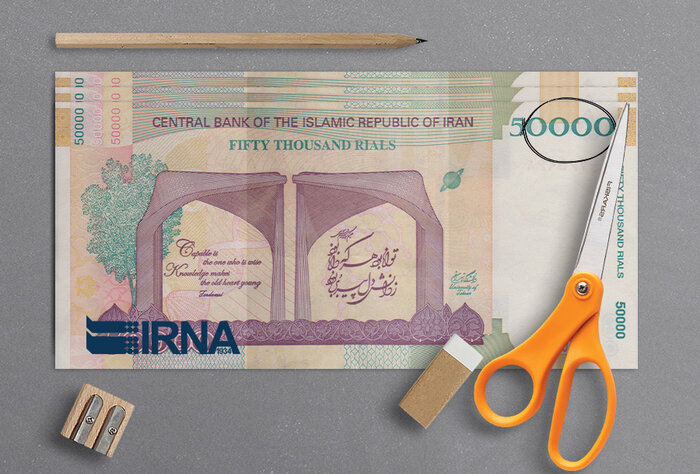

The vote itself reflected the contentious nature of the reform: 144 votes in favor, 108 against, and 3 abstentions out of 262 present representatives. The approved legislation adds a clause to Article 58 of the Central Bank Law, establishing that the new rial will equal 10,000 current rials and be divided into 100 qirans. Five critical provisions accompany this change, including rules for determining foreign currency exchange rates, a maximum three-year transitional period during which both old and new currency will circulate simultaneously, requirements for the Central Bank to prepare implementation within two years, and mandates that all past obligations be fulfilled only in the new currency after the transition period ends.

The Reality Behind the Reform: A Currency Already Abandoned by Its People

Perhaps the most telling aspect of this reform is that it merely formalizes what Iranians have been doing for years. Despite the rial being the official currency, citizens have long since abandoned it in daily conversation, preferring instead to use “toman”—an unofficial unit worth ten rials. As Central Bank Governor Mohammad Reza Farzin acknowledged: “While the official monetary unit is the rial, in practice people use the word toman and do not use rial in their transactions and conversations.”

This disconnect between official designation and practical usage reflects the deeper problem: chronic inflation has steadily eroded the currency’s value, transforming small daily purchases into transactions involving hundreds of thousands or millions of rials. The numbers have grown so unwieldy that even shopkeepers and customers automatically convert prices, mentally removing a zero without thinking. The reform attempts to bridge this gap between legal fiction and lived reality, bringing official policy in line with what the market has already decided.

The erosion of the rial’s value has created more than computational difficulties—it has become a matter of national pride. Farzin described the situation in stark terms, noting that “with increased inflation and decreased value of the national currency, the ratio of national currency value to foreign currencies has drastically declined, and this issue has also caused a decline in national pride.” When a currency requires six or seven digits to purchase basic goods while foreign currencies manage with two or three, it sends a message about economic strength—or weakness—that transcends mere mathematics.

No Magic Bullet: The Central Bank’s Candid Assessment

One of the most remarkable aspects of this reform has been the Central Bank’s unusual transparency about what it will and will not accomplish. In an era when governments often oversell policy changes, Farzin’s candor stands out. He stated explicitly: “Our goal is neither inflation control nor increasing the value of the national currency; the main function of this action is to facilitate transactions and simplify monetary calculations.”

This honest assessment sets realistic expectations. The reform will not magically restore purchasing power or halt inflation. It will not make Iranians wealthier overnight. What it will do is make the mechanics of commerce less cumbersome, reduce the cognitive load of calculating with astronomical numbers, and restore the ability to use decimal points in the national currency—something commonplace in dollars, euros, and other major currencies but absent from Iranian economic life.

Farzin further emphasized the inevitability of this change: “Although annual inflation in the country has remained stable in the range of 30 to 40 percent in recent years, continuing the current trend is no longer possible and there is no choice but to implement this reform.” With inflation persistently high, the alternative to reform is watching the numbers grow ever more absurd until the system breaks down completely.

The Central Bank governor also addressed concerns about whether the zeros would simply return. With current inflation rates, he calculated, it would take at least 35 years for the problem to recur—providing, of course, that inflation rates don’t accelerate further. This projection offers some comfort but also underscores that the reform treats symptoms rather than causes.

Implementation Challenges and International Precedents

The technical execution of this reform presents formidable challenges. The Central Bank must design and print new banknotes and mint new coins, redesign banking systems to accommodate the change, and conduct massive public education campaigns—all before implementation begins. The transition period, during which old and new currencies circulate simultaneously, represents the most difficult phase. As one report noted, this “dual currency period” is where “the slightest inaccuracy can lead to abuse or confusion.”

International experience offers both cautionary tales and success stories. Turkey removed six zeros from its currency in 2005, backed by inflation control and economic stability, and succeeded. Brazil made zero removal part of an anti-inflation package in the 1990s and won public trust. However, Venezuela and Zimbabwe removed zeros repeatedly without fundamental reforms, only to see the zeros return—each time more numerous and burdensome than before.

Experts warn that without accompanying policies to control inflation, structural budget reforms, liquidity management, and genuine central bank independence, this reform risks becoming merely “cosmetic surgery”—changing the appearance without addressing the underlying condition. As Hosseini acknowledged: “Although these reforms alone cannot affect inflation control and are not proposed as an independent monetary policy, they are unavoidable due to successive inflations and operational problems caused by the large number of zeros in the national currency.”

The chairman of the Economic Commission also pointed to regional precedents, noting that “countries like Turkey reformed their currency units twice in 2003 and 2005, without necessarily changing the name of the currency.” He added that “unfortunately today, Iran’s currency is one of the weakest currencies in terms of the number of zeros, creating computational problems for us that we must correct.”

Iran’s approval of currency reform represents a pragmatic acknowledgment that the gap between official policy and economic reality had grown too wide to ignore. By removing four zeros and reintroducing the qiran, the government is essentially codifying what Iranians have been doing informally for years. Yet the reform’s success will ultimately depend not on the elegance of its numerical simplification but on whether it accompanies—or precedes—meaningful efforts to address the chronic inflation that necessitated it in the first place. As the new currency begins its journey from parliamentary approval through Guardian Council review and eventual implementation, Iran embarks on an experiment that could either mark the beginning of restored monetary credibility or become merely a brief footnote in the country’s economic history. The coming months and years will reveal whether this technical adjustment can serve as a catalyst for broader economic reform or remains what its architects honestly admit it to be: a necessary simplification of an accounting system strained to breaking by years of inflation, offering clarity in presentation if not value in substance.