Although it is difficult to provide a comprehensive definition of complex phenomena like political parties and multiparty systems—perhaps due to the differing opinions and ideological backgrounds of scholars and researchers—this does not prevent efforts to approach an appropriate definition and understanding of the relationship between them. In this context, regarding the concept of political parties, it is essential to distinguish between two primary perspectives:

- The first perspective, rooted in Marxist thought, views political parties as nothing more than political expressions of specific social classes. According to this viewpoint, every political party represents a class and serves as a tool in the broader class struggle.

- The second perspective, grounded in liberal and democratic political literature, suggests that the formation of political parties is closely tied to the development of representative democracy. From this angle, a party is seen as an organization that nominates candidates for office, aiming to represent the electorate.

Despite the differences in these definitions, some scholars have attempted to connect the concept of political parties to the phenomenon of power. In this view, a political party is an organization that seeks to attain power, whether within a democratic or undemocratic system. From this perspective, scholars argue that the ultimate goal of a political party is not merely to achieve power for its own sake, but to dominate—or at the very least, participate in—the formulation and implementation of public policy in the country.

In addition to the primary objective of gaining power, political parties are expected to perform several other important functions, such as: representing the desires and interests of the masses, shaping and guiding public opinion, training cadres and producing political leaders, and creating an organized opposition. Beyond these functions, some researchers suggest that political parties, like the media, public gatherings, and mass organizations, serve as tools for freedom of expression and belief. In this light, some define a political party as a group of people united by their shared commitment to a specific ideology or belief system.

In general, most experts agree that political parties, as we know them today, are a relatively recent phenomenon, having existed for no more than 150 to 200 years. Of the 194 recognized countries in the world, 179 have political parties, while only 15 countries—such as Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the Vatican—either do not allow political parties or do not have any.

Based on the global role of political parties, scholars typically classify the political systems of countries with party politics into three main types, according to the number of active political parties:

- One-party system: This system permits the existence of only one political party, with little or no political participation from other groups. Seven countries currently operate under such systems, including Eritrea, Cuba, Turkmenistan, China, North Korea, Laos, and Vietnam.

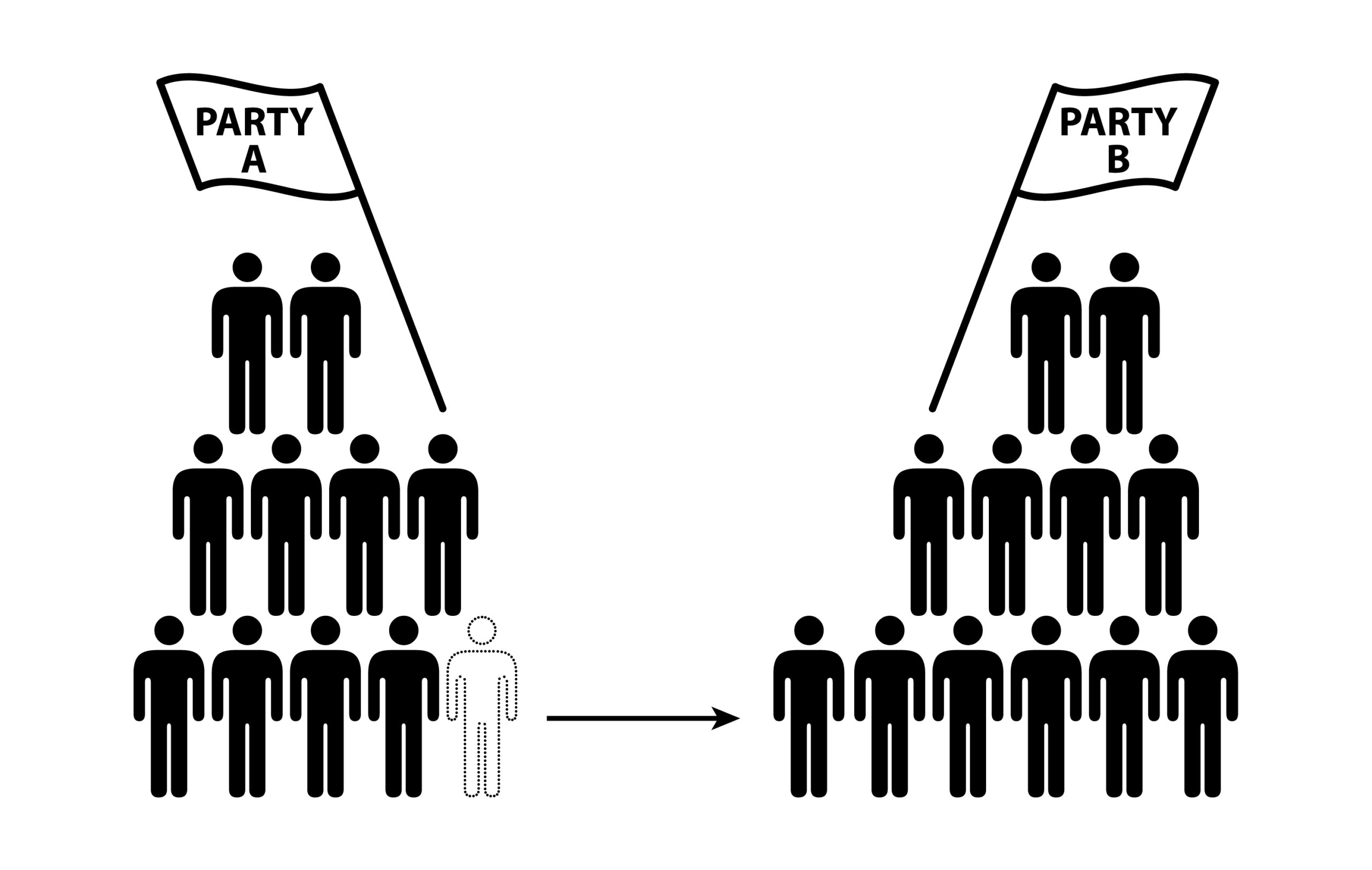

- Two-party system: In this system, two dominant political parties become the focal point of most political activities. While other parties may exist, they have little influence on the political landscape. This system is found in approximately 26 countries, including the UK, the US, Malta, Spain, Liechtenstein, Mozambique, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Sri Lanka, among others.

- Multi-party system: In this system, three or more political parties compete for power and governance. Most countries in the world follow this type of system, which exists in around 146 nations, such as Switzerland, Norway, the Netherlands, Denmark, Turkey, India, Lebanon, Argentina, Brazil, Morocco, Cameroon, and South Africa. Among these, 32 countries operate under a variant called the dominant-party system. This is still considered a multi-party system, but one party frequently wins the majority of seats in parliament across several consecutive elections, allowing it to govern alone for extended periods.

From this classification and the globalization of political parties, many scholars recognize a strong connection between the concept of political parties and multipartyism. Joining a party and participating in party activities—within the legal boundaries of the right to expression, freedom of assembly, and freedom of opinion—reflects the various ideological, social, class, ethnic, national, and religious divisions within a society. However, in its specific sense, multipartyism refers to a system where three or more political parties actively compete for power.

In contrast, countries with single-party systems or those that do not permit political party activities do not allow for the implementation of multipartyism in the general sense. Of the 194 countries mentioned, only 22, or approximately 11.4%, do not practice multipartyism. Meanwhile, 172 countries, roughly 88.6% of the world’s nations, practice multipartyism or two-party systems at different levels.

In line with the views of French scholar Maurice Duverger, who argued that the growth of political parties throughout history is linked to the expansion of democracy and the right to vote, multipartyism represents another form of freedom of expression and political pluralism. It guarantees the right for all social groups—whether based on ideology, ethnicity, nationality, or religion—to participate in the political process. The concept of pluralism itself, as a political philosophy, is rooted in recognizing and respecting diversity within a political society. This promotes tolerance and peaceful coexistence among differing interests, beliefs, and lifestyles.

However, according to the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), political parties in many countries still face significant challenges, such as inadequate budgets, weak legitimacy among citizens, unequal access to media, and restrictions on their activities. These obstacles hinder the exercise of rights and freedoms in multiparty systems.

Another notable phenomenon is the decline of political parties in public life, a trend observed by researchers, particularly among younger generations—not only in developing nations but also in advanced democracies. In countries like the United States and Europe, major political parties are experiencing a weakening relationship with the public, leading to a decline in their popular support. Several factors contribute to this decline, including accusations of corruption against elected officials, decreasing party membership, widespread disenchantment with party politics, and lower voter turnout.

This trend has paved the way for the rise of moderate and reformist parties, which often seek to appeal to a broad base by avoiding radical solutions and focusing on compromise. However, it has also led to the emergence of extremist nationalist movements and populist leaders advocating for rapid, often violent changes.

At the same time, the revolution in communication and media, particularly the rise of the internet and social media, has opened countless channels for public expression, diminishing the traditional role of political parties in this domain. As a result, the link between multipartyism and political pluralism is likely to weaken over time.

References:

- موریس دیفرجیة، الاحزاب السیاسیة، ترجمة: علب مقلد و عبد المحسن سعد، الهیئة العامة لقصور الثقافة، القاهرة، ٢٠١١، ص ص ٦-١٩.

- أ.م.د.هادي مشعان ربيع، التعددية السياسية وعلاقتها بالتعددية الحزبية، مجلة القانون الدستوري والمؤسسات السياسية، الجزائر، العدد ١، المجلد ١، ٢٠١٧، ص ص ٢١٧-٢١٩.

- Scruton, Roger. (2007). The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought (3rd ed.). PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, New York, pp. 510-511, 528.

- Robertson, David. (2004). The Routledge Dictionary of Politics (3rd ed.). University of Oxford, Taylor & Francis Group, New York, pp. 326-327, 373-374, 380-381, 445-446, 488-489.

- (2011). Good governance requires vibrant political parties, pluralism, participants at OSCE meeting say. Available at: https://www.osce.org/odihr/77704.

-

This article was authored by (Dr. Abid Khalid Rasool) and published in the Journal of Future Studies (JFS) in Kurdish. It has been translated by (Hevar Sherzad) for Kfuture.Media.